ONE FROM THE HEART: THE GASPAR NOE INTERVIEW

Wednesday, September 16, 2015 at 6:15AM

Wednesday, September 16, 2015 at 6:15AM ‘Sentimental’ is not a word often bandied about when discussing the films of Gaspar Noe, but the director of such envelope-pushers as I Stand Alone, Irreversible and Enter the Void is out to change a few minds with his latest film, Love. “This is a movie that has made a lot of people cry,” he tells SCREEN-SPACE from his home in Paris, as the Sydney Underground Film Festival organisers brace themselves for reaction to the Opening Night screening of the latest from the ‘enfant terrible’ of international cinema...

“I wanted to do a melodrama,” explains the 51 year-old Argentinian-born, French-based filmmaker, who premiered the long-in-development drama at Cannes 2015. “I envisioned the movie as both very arousing and also very sad, with the hope that people would cry at the end. It became much more melancholic than what I thought because image is so much more powerful than text. The movie is best described as being made up of my desires and fears.”

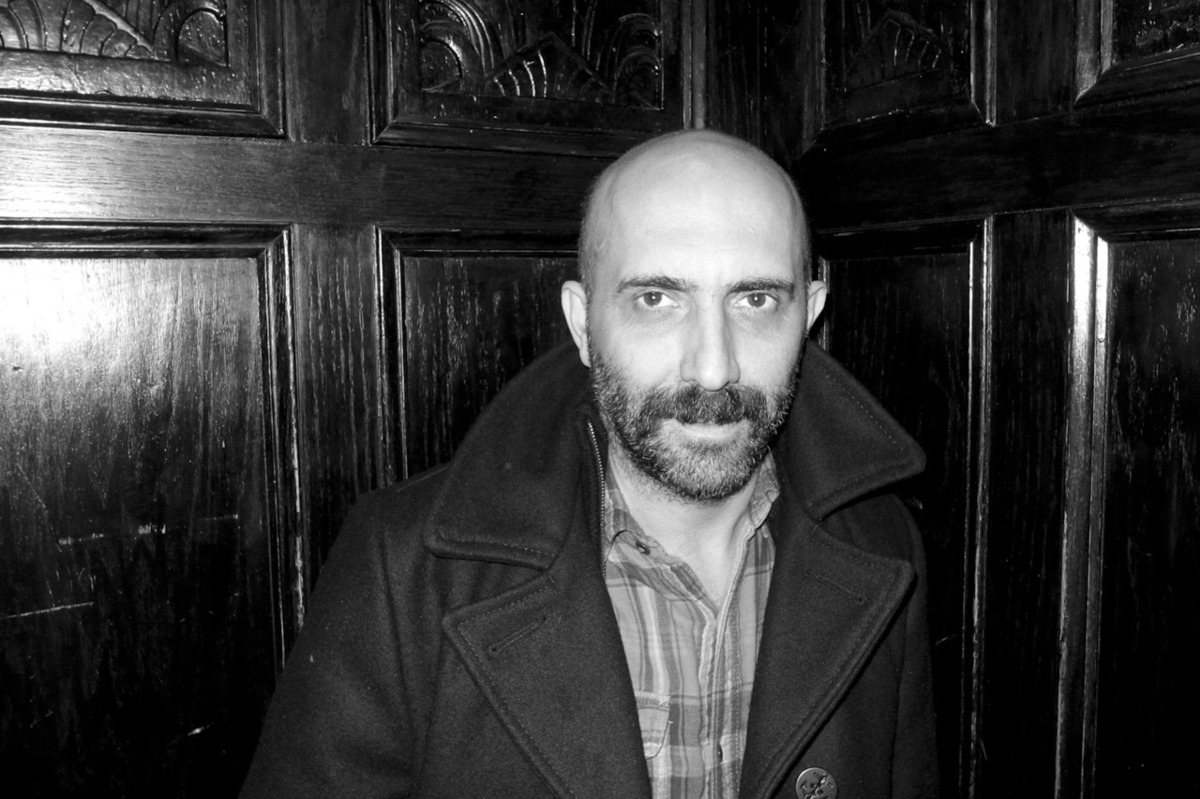

Drawing upon his days as a film school student cutting a swathe through the bars and bedrooms of 1980s Paris, the auteur’s narrative follows brash American expat Murphy (Karl Glusman) as he recalls the passionate details of a doomed love affair with the sexually energized Electra (Aomi Muyock; pictured, with Glusman), while coping with the corrosive resentment he has for his young wife, Omi (Klara Kristin). “‘Murphy’ is a mix of me and my film school mates, who I would hang out with and party with. And I know certain characters who [populate] the movie, people from the party scene in Paris and the art world,” explains Noe. “I wanted this guy to be cool but also a bit stupid; he’s not a ‘winner’ at all. He’s just a normal film student, sometimes driven by his brain cells and sometimes driven by his dick.”

Drawing upon his days as a film school student cutting a swathe through the bars and bedrooms of 1980s Paris, the auteur’s narrative follows brash American expat Murphy (Karl Glusman) as he recalls the passionate details of a doomed love affair with the sexually energized Electra (Aomi Muyock; pictured, with Glusman), while coping with the corrosive resentment he has for his young wife, Omi (Klara Kristin). “‘Murphy’ is a mix of me and my film school mates, who I would hang out with and party with. And I know certain characters who [populate] the movie, people from the party scene in Paris and the art world,” explains Noe. “I wanted this guy to be cool but also a bit stupid; he’s not a ‘winner’ at all. He’s just a normal film student, sometimes driven by his brain cells and sometimes driven by his dick.”

Over a decade ago, the project was pitched to then husband-and-wife stars Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel when the pair worked with Noe on Irreversible, the 2002 revenge drama famous for Noe’s notorious single-shot rape scene. But the international stars baulked at the director’s intention to shoot full penetration intercourse. By 2015, Noe’s creative impulses were sated, with Glusman and first-time actors Muyock and Kristin portraying graphic, reportedly unchoreographed sexual acts (in 3D, no less). The film opens with an extended single-take scene of oral sex and mutual masturbation, from beginning to end.

“Erotic cinema has disappeared, and with it the erotic malady,” observes Noe. “The point of this movie, the reason it exists, was to portray the passion between two willful young people. I could not see how you could film that nowadays, after the sexual revolution and after the past 40 or so years of our western world, without portraying exactly how it is in real life. I decided that now is the time to film scenes with a truthfulness that the subject of my movie deserves. I’m surprised there are not more movies dealing with the subject like my film does”

“Erotic cinema has disappeared, and with it the erotic malady,” observes Noe. “The point of this movie, the reason it exists, was to portray the passion between two willful young people. I could not see how you could film that nowadays, after the sexual revolution and after the past 40 or so years of our western world, without portraying exactly how it is in real life. I decided that now is the time to film scenes with a truthfulness that the subject of my movie deserves. I’m surprised there are not more movies dealing with the subject like my film does”

It is the search for the blunt truths of existence that have driven Noe’s works to date; in his last film, Enter the Void, his first-person camera examined a body’s demise and the re-emergence of its soul. Love represents a similar pathway from the dual perspective of emotion and sensation. “These natural desires that we have, to have the faith to give our lives and share our journey with someone else, produce very human, powerful emotions,” says Noe. “Most people recognise much about themselves in the characters in the film and about the experience of being in love.”

Noe achieves his thematic goals by expanding upon the reverse-storytelling device that he employed in Irreversible (pictured, right; star, Monica Bellucci). Initially, Murphy’s present-day inner thoughts narrate small recollections; ultimately, the entire film is given over to his indulgences in the past. “The whole way [Love] was structured was to try to reproduce a memory. When you think about your own past, you do not do it in a linear way,” Noe explains. “In Irreversible, the backwards storytelling was very mechanical, in a clockwork way; in Enter The Void, the journey was very linear. In Love, it gets as close as I’ve gotten to that ‘stream of memory’ framework.”

Noe achieves his thematic goals by expanding upon the reverse-storytelling device that he employed in Irreversible (pictured, right; star, Monica Bellucci). Initially, Murphy’s present-day inner thoughts narrate small recollections; ultimately, the entire film is given over to his indulgences in the past. “The whole way [Love] was structured was to try to reproduce a memory. When you think about your own past, you do not do it in a linear way,” Noe explains. “In Irreversible, the backwards storytelling was very mechanical, in a clockwork way; in Enter The Void, the journey was very linear. In Love, it gets as close as I’ve gotten to that ‘stream of memory’ framework.”

As confronting as Gaspar Noe’s visions have been, each has represented a yearning to explore and further understand base elements inherent to the human experience. As shocking as scenes of frank sexuality may be to many, it is what the images represent that matters most to the director. “I wanted to make a sentimental film about what love is, how hard love is, to show that, even with the best intentions in the world, love can fail and ultimately destroy your mind,” he says. “To be addicted to passion means that you can suffer through passion and your life is over. I needed to find a way to portray this power, a power that can consume and destroy your life. What is the truest aim of our existence? I think it is to find love and to share the strongest physical love with someone, and my film explores that.”

LOVE screens as the Opening Night presentation of the 2015 Sydney Underground Film Festival. Full venue and session information can be found at the official website.

3D,

3D,  Extreme Cinema,

Extreme Cinema,  French Cinema,

French Cinema,  Gaspar Noe,

Gaspar Noe,  Love,

Love,  SUFF,

SUFF,  Sex in Film

Sex in Film