THE SHELTER: THE MICHAEL PARE INTERVIEW

Wednesday, December 16, 2015 at 6:23AM

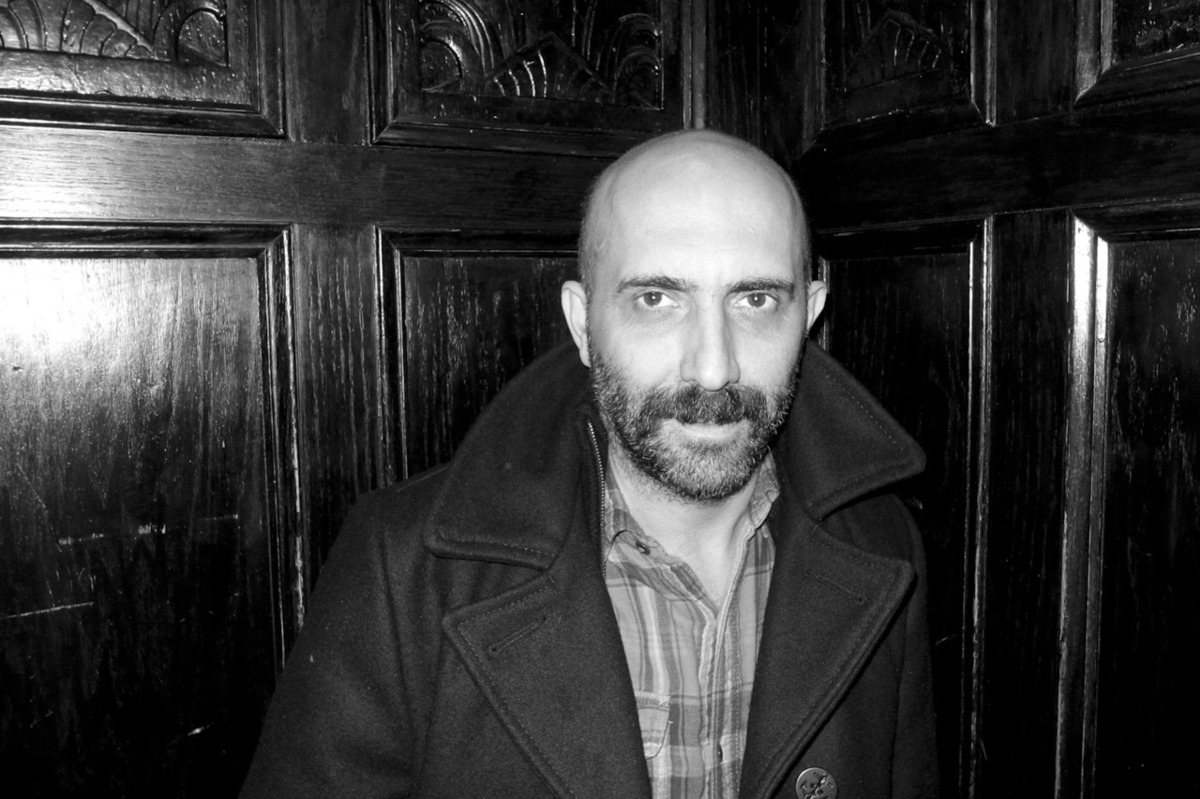

Wednesday, December 16, 2015 at 6:23AM Michael Paré is a rare talent, embodying the phrase ‘a great character actor in a leading man’s body’. His iconic roles – Tom Cody in Streets of Fire; Eddie in Eddie and The Cruisers; David in The Philadelphia Experiment – are recalled with reverential glee by a generation of moviegoers. Since those heady days, the Brooklyn native has worked ceaselessly, alongside such eclectic filmmaking talents as Roland Emmerich (Moon 44), Eric Red (Bad Moon; 100 Feet), John Carpenter (Village of The Damned), Uwe Boll (BloodRayne; Seed) and Sofia Coppola (The Virgin Suicides). His latest is The Shelter, writer/director John Fallon’s dramatic psychological-thriller. Following the film’s recent screening at A Night of Horror Film Festival (ANOH) in Sydney, organisers determined that the time was right to honour Michael Paré for his contribution to cinema; he became the inaugural recipient of the event’s Career Achievement Award.

In the wake of the honour, Paré spoke with SCREEN-SPACE editor (and ANOH Jury President) Simon Foster from his LA home about his latest film, the actors who still inspire him and the time he spent Down Under…

Before we focus in on The Shelter, I want to ask you about Undercover, an Australian film you made what must feel like a hundred years ago. How did you end up in director David Steven’s comedy about women’s underwear?

(Laughs) Well, David was in LA casting and I got sent the script, right after I’d done Eddie and The Cruisers. I thought, ‘Wow, a period piece,’ but one that wasn’t rock’n’roll and wasn’t action and seemed like a lot fun. I met David but I was a day late for the audition, he was getting ready to leave to fly home. And he gave me the job. It was my first job outside of the US. I needed to get a passport to make this film on the other side of the planet. I loved the experience; it was great time. I wish I could get back to Australia to work again. (Pictured, right; Paré with co-star Genevieve Picot in 1983's Undercover)

(Laughs) Well, David was in LA casting and I got sent the script, right after I’d done Eddie and The Cruisers. I thought, ‘Wow, a period piece,’ but one that wasn’t rock’n’roll and wasn’t action and seemed like a lot fun. I met David but I was a day late for the audition, he was getting ready to leave to fly home. And he gave me the job. It was my first job outside of the US. I needed to get a passport to make this film on the other side of the planet. I loved the experience; it was great time. I wish I could get back to Australia to work again. (Pictured, right; Paré with co-star Genevieve Picot in 1983's Undercover)

The Career Achievement honour at A Night of Horror was inspired by your performance in The Shelter. The complexity of your performance reflects a dedication to the craft nurtured over time. It is among your best work…

Thanks a lot, it was a great pleasure. It was a thing of love, not something that anyone thought was going to be very commercial. But it is a very dramatic story, great cinematography and a very impassioned crew and cast. It was a great experience.

Your character, Thomas, goes through a vast arc - guilt, grief, corrosive memories, the quest for redemption. Tell me about your impressions of the character when you first read John’s script…

The pain and suffering that a person can bring on themselves, the cost of not being aware of the impact of your actions on others; that misery and suffering and despair and guilt and remorse. These are incredibly powerful and painful emotions to experience. And they were brought on Thomas by his own actions, his own weakness. Not to pontificate, but a lot of pain and suffering is brought on by one’s own behaviour and it’s very sad. Nobody has to punish you, (yet) you often do it to yourself. It is an amazing thing to see. It is an interesting thing for me to explore, because I play a lot of heroes, cop stuff and detective stuff. But this was a small movie, filled with humanity.

The pain and suffering that a person can bring on themselves, the cost of not being aware of the impact of your actions on others; that misery and suffering and despair and guilt and remorse. These are incredibly powerful and painful emotions to experience. And they were brought on Thomas by his own actions, his own weakness. Not to pontificate, but a lot of pain and suffering is brought on by one’s own behaviour and it’s very sad. Nobody has to punish you, (yet) you often do it to yourself. It is an amazing thing to see. It is an interesting thing for me to explore, because I play a lot of heroes, cop stuff and detective stuff. But this was a small movie, filled with humanity.

How close did your interpretation of Thomas mesh with John’s vision?

The facts were all in the script. How they were going to manifest through me, the actor, hadn’t been worked out, of course. But John had seen a lot of my work and we were kind of buddies. He was there when we shot Bad Moon; he was with us in Hungary when we shot 100 Feet. Our mutual friend, Eric Red, and John and I have spent a lot of time together. So just talking with him about this subject matter, John could tell that I understood what he was going for. (Pictured, right: producer Donny Broussard, director John Fallon with Paré on the set of The Shelter)

The facts were all in the script. How they were going to manifest through me, the actor, hadn’t been worked out, of course. But John had seen a lot of my work and we were kind of buddies. He was there when we shot Bad Moon; he was with us in Hungary when we shot 100 Feet. Our mutual friend, Eric Red, and John and I have spent a lot of time together. So just talking with him about this subject matter, John could tell that I understood what he was going for. (Pictured, right: producer Donny Broussard, director John Fallon with Paré on the set of The Shelter)

I know your acting heroes are Brando and Dean; am I right in observing there is some of their dedication to character in your performance?

I didn’t try to imitate any other actor but I admired their performances so much and that they gave up so much of their souls to be photographed. So when you see such a powerful guy like Marlon Brando collapse in front of the apartment in A Streetcar Named Desire because he is so lonely and desperate and hungry for Stella, to see this brute is also such a baby. To find this strong, physical guy is so emotionally handicapped (means) a strong similarity between Stanley and Thomas exists. And in Rebel Without a Cause, Dean has that great scene when he’s watching his parents fight and he has that great line, “You’re tearing me apart,” because he cant figure out what is right or wrong anymore. Yeah, that’s inspiring. That’s Jimmy Dean, the coolest man in the world at the time and he’s willing to show this incredible vulnerability. So, yes, inspiration but not imitation.

Whether it’s the big studio pictures like The Lincoln Lawyer or the Uwe Boll stuff or smaller, prestige pics like The Shelter, 121 IMDb credits suggests an incredible work ethic. How would you sum up your philosophy of your craft and the industry you’ve been part of for so long?

It doesn’t matter what size the budget is, my job as an actor is the same. I have to do my preparation, be on time, hit my marks and create a performance. The tape on the floor isn’t that expensive (laughs). Whether it’s a $50,000 camera or some little handheld thing, my job’s the same. Ask any thespian; when they step on stage in some little town in the middle of nowhere, it is the same as stepping on a stage anywhere. The audiences might be big or small, the projects are never the same, but the job is always the same.

Horror,

Horror,  Independent Film,

Independent Film,  John Fallon,

John Fallon,  Michael Paré,

Michael Paré,  The Shelter

The Shelter