KRRISH 3

Wednesday, November 6, 2013 at 11:32PM

Wednesday, November 6, 2013 at 11:32PM Stars: Hrithik Roshan, Kangana Ranaut, Priyanka Chopra and Vivek Oberoi.

Writers: Robin Bhatt, Honey Irani, Irfan Kamal, Akarsh Khurana, Sanjay Masoom and Rakesh Roshan.

Director: Rakesh Roshan.

Rating: 3/5

Exhibiting ten movies worth of good-vs-evil comic-hero conflict and positively drenched in the glorious morality synonymous with India’s Diwali celebration, Rakesh Roshan’s Krrish 3 is the type of big Bollywood blockbuster that can both delight and infuriate western audiences. Domestic crowds, however, will be thrilled by the latest adventures of their own ‘Man of Steel’, whose pure family values and washboard abs are made for the biggest cinema-going week of the Indian year.

The four-quadrant action melodrama has already displaced Shah Rukh Khan’s Chennai Express as the fastest-earner over the first five days of its run, with ₹134.87 crore banked. The Hindi heroics are also playing strongly in Tamil and Telugu dialects, putting Krrish 3 on course for a record-setting season; if it stays on track, analysts suggest it may emerge as the top-grossing Indian film of all time.

Having firmly established the mythology with the first instalment, 2003’s alien-meets-boy hit Koi…Mil Gay, before fully launching star Hrithik Roshan’s titular alter-ego in 2006’s Krrish, the third instalment unleashes the black-leather do-gooder in full super-hero mode. Sharing his secret identity with his doddering scientist father Rohit (also Roshan, thoroughly convincing in old-age make-up) and sweetheart, journalist Priya (Priyanka Chopra, in the Lois Lane role), nice-guy Krishna Mehra smiles through life’s hardships as he tries to hold down a regular job. Having to regularly soar high above Mumbai to save those in peril plays havoc with your attendance record, apparently…

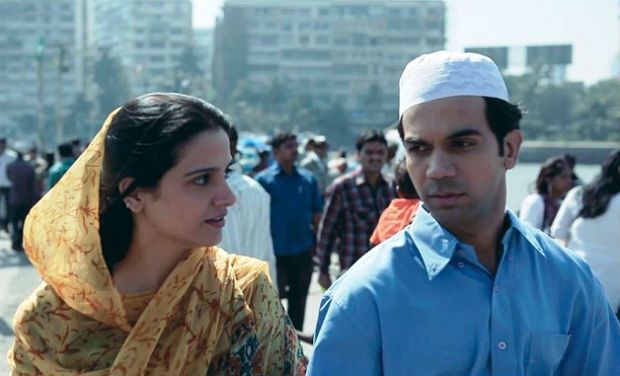

But true evil has surfaced in the form of Kaal (Vivek Oberoi, chewing scenery like termites), a seething whellchair-bound telekinetic who, with his band of mutant henchmen led by shape-shifting stunner Kaya (Kangna Ranaut, a standout), is planning to poison the cities population. As expected, the labyrinthine plot convolutes in on itself, working in father-son angst, jealousy, betrayal and retribution along with the potentially fatal biohazard weapon before a seemingly endless final reel confrontation between Krrish and Kaal lays waste to most of downtown Mumbai.

The Bollywood sector’s penchant for pilfering the most effective elements of their LA counterpart’s biggest hits has been largely dormant of late, but Roshan corrects the balance in one fell swoop with Krrish 3. References to the X-Men films and Christopher Nolan's Inception abound, as do not-so-subtle nods to World War Z, The Avengers, Spider Man, Thor and the aforementioned Superman reboot. That said, the use of the familiar components is done with flair and technical dexterity, ensuring Krrish 3 is every bit (and, occasionally, a whole lot more) enjoyable than the originals.

A tighter third act would have helped, with one too many teary farewells and resurrected bad-guys bulking up the finale. Naturally, such issues won’t bother the under-12s, for whom this old-fashioned, energetic matinee malarkey is clearly aimed; at one point, our hero saves a young ‘un and informs him that Krrish lives in all those who chose to do good.

Musical numbers are generally infectious, with the pick of them being the giddy staging of ‘Raghupati Raghav’.