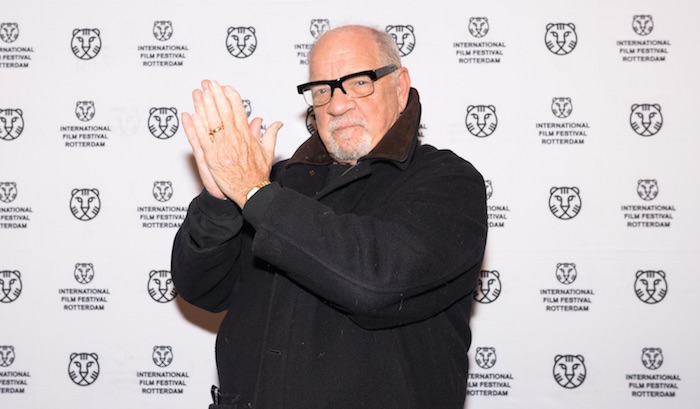

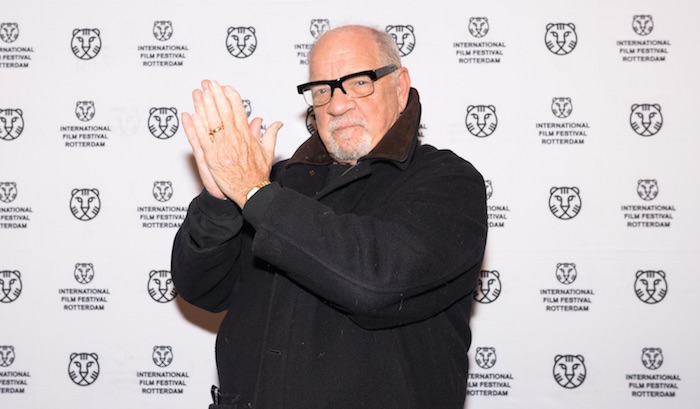

IFFR 2018: The setting provided to meet with Paul Schrader is appropriately magisterial. A corner boardroom, high-walled and white carpeted, near the third floor film festival offices in Rotterdam’s de Doelen building, has been turned into bare space; tall windows allow the steely grey morning light to fill the room. The 72 year-old industry icon sits alone at a small table in the far corner, checking his phone; despite the imposing space he commands, Schrader appears, in every respect, to be a respectable if unremarkable elderly gentleman. But his legacy is remarkable; after half a century as a gifted screenwriter (Taxi Driver; Rolling Thunder; Obsession; The Mosquito Coast; The Last Temptation of Christ; Bringing Out the Dead) and director, often of his own scripts (Hardcore; American Gigolo; Cat People; Mishima A Life in Four Chapters; Affliction; Auto Focus; The Canyons), his immense reputation fills the room.

Schrader is attending the International Film Festival Rotterdam with his latest film First Reformed, a dark spiritual journey in which a damaged chaplain (Ethan Hawke) crusades via increasingly desperate means for environmental change. He is also presenting ‘Dark and the Lessons Learned’, a frank account of his torrid experiences shooting, relinquishing, then resurrecting his 2014 Nicholas Cage thriller, Dying of The Light. His handshake is soft; his voice strong, if a little congested. Thankfully, Paul Schrader, once considered one of Hollywood’s darker personalities, is in a good mood. By the time SCREEN-SPACE settled into the chair opposite him, he was already talking movies…

SCREEN-SPACE: You come to Rotterdam on a wave of good will for First Reformed, which is getting some of the best reviews of your career.

SCREEN-SPACE: You come to Rotterdam on a wave of good will for First Reformed, which is getting some of the best reviews of your career.

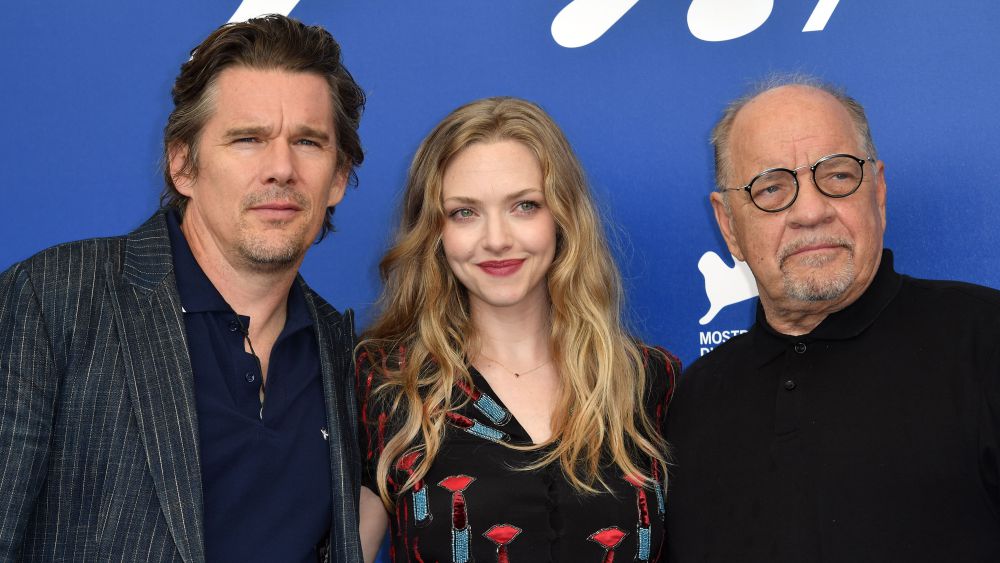

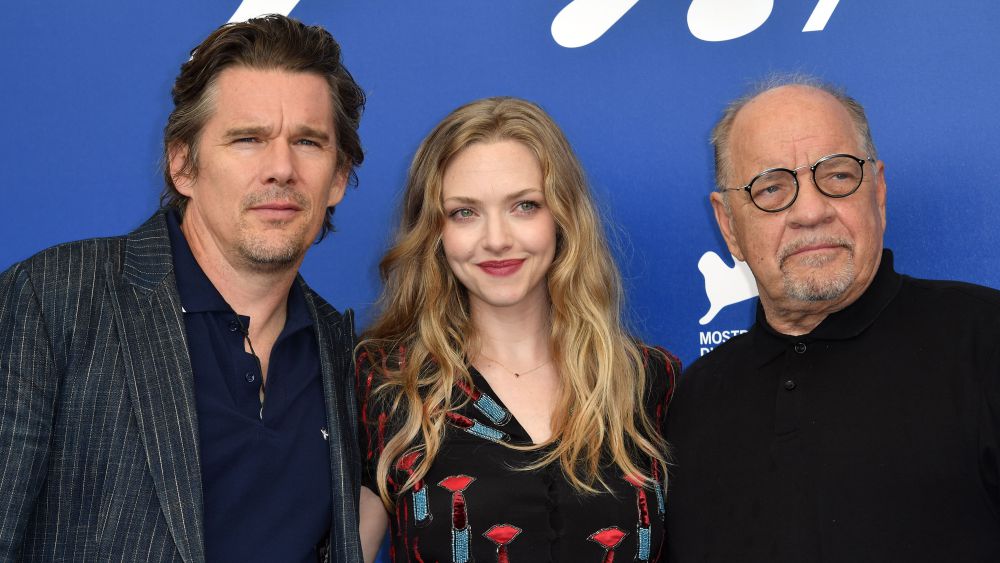

SCHRADER: I’ve not had a bad screening of this film. It seems to work for people. In fact, because the film pulls so many things together, themes that I’ve worked with over the last 15 years – writing about spiritual things, making spiritual films – I’ve decided to enjoy this moment, this victory lap of touring around the world with the film. I’m doing a whole lecture tour at various seminaries around the US. I’ve updated a book that I wrote 45 years ago, called Transcendental Style in Film, and that gets republished in May. (Pictured, above; First Reformed stars Ethan Hawke, left, and Amanda Seyfried, with their director)

SCREEN-SPACE: Is this the first time you’ve ever fully explored in film what you wrote about in your book?

SCHRADER: It’s the first time I’ve ever had the desire to. It came about maybe 3 years ago. I was giving an award to Pawel Pawlikowski for his film Ida and we had dinner together, and I was taken back by how much I liked [Ida], responded to its themes and story. And I was alone, walking home, and just said out loud to myself, “It’s time you made one of these.” I had never thought I would make a contemplative film, but after that dinner with Pawel it struck me that I was 70 years old and that I should make one.

SCREEN-SPACE: How did that desire manifest through the lead character Toller, played by Ethan Hawke? How is your contemplative protagonist different from other Schrader leads?

SCHRADER: The main character stems from Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest. The setting is from Bergman’s Winter Light; there’s a levitation scene I’ve taken from Tarkovsky. The ending, sort of from Borzage. And it’s all held together by the glue of Taxi Driver (laughs). Toller is a sick man, his main sickness being what Kierkegaard called ‘the sickness unto death’, which is despair and angst. He is trying to find any way he can through his sickness, be it drink or keeping his journal or the ritual of church services. When he meets this kid with another kind of despair, a sad resignation about the environment, he tries to counsel the kid but the kid kills himself. So Toller adopts the boy’s sickness, adapts it into his own despair, and becomes an environmentalist jihadist. Now, that despair has become much more immediate in our current times. In the past, 2000 years ago, when mankind spoke about the future they spoke hypothetically, will no real notion of the end of days. Nowadays, such discussions are not so hypothetical. (Pictured above; Ethan Hawke as Toller, in First Reformed)

SCHRADER: The main character stems from Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest. The setting is from Bergman’s Winter Light; there’s a levitation scene I’ve taken from Tarkovsky. The ending, sort of from Borzage. And it’s all held together by the glue of Taxi Driver (laughs). Toller is a sick man, his main sickness being what Kierkegaard called ‘the sickness unto death’, which is despair and angst. He is trying to find any way he can through his sickness, be it drink or keeping his journal or the ritual of church services. When he meets this kid with another kind of despair, a sad resignation about the environment, he tries to counsel the kid but the kid kills himself. So Toller adopts the boy’s sickness, adapts it into his own despair, and becomes an environmentalist jihadist. Now, that despair has become much more immediate in our current times. In the past, 2000 years ago, when mankind spoke about the future they spoke hypothetically, will no real notion of the end of days. Nowadays, such discussions are not so hypothetical. (Pictured above; Ethan Hawke as Toller, in First Reformed)

SCREEN-SPACE: Let me read from Owen Gleiberman’s Variety review, in which he states your film exhibits, “the transcendental austerity of Bresson, Dreyer and Ozu”. What does it mean to be spoken of in that sort of company?

SCREEN-SPACE: Let me read from Owen Gleiberman’s Variety review, in which he states your film exhibits, “the transcendental austerity of Bresson, Dreyer and Ozu”. What does it mean to be spoken of in that sort of company?

SCHRADER: It is a contemplative film. Most films lean into you, are desperate for your attention. Here’s a beautiful naked person, here’s some loud music to tell you how to feel. Another way a film can work, the way I think and hope First Reformed works, is to lean away from you. They give you less, slow it down, delay the cuts, don’t have music. When movies lean away, which is inherently an uncommercial thing to do, then the viewer can lean into the film, or they can leave. That’s the delicate dance that a filmmaker who works on the slow side has to do. Asking of yourself, ‘How can I slow it down? How can I withhold things from you and get you to come and join this story without boring you? Or at least boring you too much.’ (Laughs) (Pictured, above; Robert Bresson)

SCREEN-SPACE: I find it interesting that both you and your Taxi Driver collaborator Martin Scorsese, with his recent film Silence, have turned to the spiritual, contemplative narrative at this point in your creative lives…

SCHRADER: That was material I had once considered. After Mishima, producers in Japan asked if there was something I would like to do in their country. I knew that Marty had let the rights lapse on that book and I never thought he was ever going to make it. So I tried to secure it, but he caught me.

SCREEN-SPACE: When I spoke with Bret Easton Ellis about The Canyons, he said, “Schrader is a drill sargeant on the set and a lot of crazy as well, but all in a good way.” Does that sum up your directorial mantra?

SCREEN-SPACE: When I spoke with Bret Easton Ellis about The Canyons, he said, “Schrader is a drill sargeant on the set and a lot of crazy as well, but all in a good way.” Does that sum up your directorial mantra?

SCHRADER: (Laughs) A film set is not a democracy and has to move very efficiently. Directors tend to be alpha types, whether male or female. You don’t really get recessive personality types becoming directors. And that is what’s expected of you, to be decisive and driven. You don’t want a drill sargeant who says, ‘What should we do today?’ Today, a film shoot goes so fast. A shoot that would’ve once been 40 days is now a 20-day shoot, and you have more footage. Someone like Ethan prefers the pace, because he says he never leaves ‘the zone’. A long shoot has a lot of dead time, whereas at the modern pace you just work, work, work. (Pictured, left; Schrader, centre, directing The Canyons)

SCREEN-SPACE: You have spent the last two decades writing narratives for the more mature leading man. Ethan Hawke, two films with Nicholas Cage, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Nick Nolte, the late James Coburn. Given the key demographic for the Hollywood suits are the under 25s, dealing with the financiers must be a challenge?

SCHRADER: I don’t think a film should unnecessarily expose anyone to financial risk. It should fit within key financial parameters. If I make a film like First Reformed, it has to have a certain budget. Whether it fails or succeeds commercially, we shot it responsibly. If I keep my budget down, that affords me the freedom to do things that other people can’t do, work that I find creatively interesting. Also, we are moving away from the theatrical distribution model, which, frankly, I don’t think is a necessarily bad thing. We have had theatrical distribution solely as a means by which to monetize movies, and it’s been the best way to do it for 100 years. Now, I’m thinking it’s not the best, most efficient way to do it. The theatre experience came out of a certain environment, and now there’s a different environment. For a film like First Reformed, which operates on the quiet side, it is good to start the conversation in a theatre. Critics should see it in a theatre; festival audiences will appreciate it in a theatre. But once the identity of the film is established, audiences can watch it anywhere that works for them. (Pictured, above; Nick Nolte, left, and Schrader on the set of Affliction)

SCHRADER: I don’t think a film should unnecessarily expose anyone to financial risk. It should fit within key financial parameters. If I make a film like First Reformed, it has to have a certain budget. Whether it fails or succeeds commercially, we shot it responsibly. If I keep my budget down, that affords me the freedom to do things that other people can’t do, work that I find creatively interesting. Also, we are moving away from the theatrical distribution model, which, frankly, I don’t think is a necessarily bad thing. We have had theatrical distribution solely as a means by which to monetize movies, and it’s been the best way to do it for 100 years. Now, I’m thinking it’s not the best, most efficient way to do it. The theatre experience came out of a certain environment, and now there’s a different environment. For a film like First Reformed, which operates on the quiet side, it is good to start the conversation in a theatre. Critics should see it in a theatre; festival audiences will appreciate it in a theatre. But once the identity of the film is established, audiences can watch it anywhere that works for them. (Pictured, above; Nick Nolte, left, and Schrader on the set of Affliction)

SCREEN-SPACE: During your Masterclass, you derided a new breed of producer, one central to the horrible experience you had on Dying of The Light. Surely the ‘just-in-it-for-the-money’ producer is not a new Hollywood thing to a seasoned veteran such as you?

SCREEN-SPACE: During your Masterclass, you derided a new breed of producer, one central to the horrible experience you had on Dying of The Light. Surely the ‘just-in-it-for-the-money’ producer is not a new Hollywood thing to a seasoned veteran such as you?

SCHRADER: It is a new Hollywood thing. In the past, people came to filmmaking through filmmaking, rising through the ranks of production companies or agencies or television, some entity within the community. Now, you are getting investors who really aren’t film people, who don’t watch a lot of movies. In the past, if you ran a film company, you were a film person. Now, the executives come from Coca-Cola, or from a toy company; people that just move from one boardroom to the next. I started out in the studio system, the first five films I did were studio pictures. But by the 80s the studios had changed, so I started making independent films. And now, the independent world is changing and you are doing essentially ‘internet films’. (Pictured, above; Nicholas Cage in Dying of The Light)

SCREEN-SPACE: I find it fascinating that so many of your films - Hardcore, Cat People, Mishima, Light of Day, Light Sleeper, Auto Focus - didn’t find favour with critics or audiences, yet have this enduring quality that makes them resonate today. What aspect of your storytelling gives these films such a life?

SCREEN-SPACE: I find it fascinating that so many of your films - Hardcore, Cat People, Mishima, Light of Day, Light Sleeper, Auto Focus - didn’t find favour with critics or audiences, yet have this enduring quality that makes them resonate today. What aspect of your storytelling gives these films such a life?

SCHRADER: I guess because they are singular. There’s only one film like Mishima. There’s certainly only one film like Auto Focus (laughs). They don’t blend into the landscape. Taxi Driver still stands out there. They are idiosyncratic; perhaps engage the mind more actively. A film like Patty Hearst, which is essentially about a person in a closet, doesn’t happen much. (Pictured, above; Schrader, left, directing Michael J. Fox and Joan Jett in Light of Day)

SCREEN-SPACE: Finally, please indulge me a story about the version of Close Encounters of The Third Kind that you wrote called Kingdom Come. An extraordinary script that Mr Spielberg perhaps did not fully appreciate…

SCHRADER: Oh, gosh. I remember when I met with Steven on it, which became an argumentative discussion. I had partly based the lead character on St Paul, a guy who debunked extra-terrestrial stories but has his own Road to Damascus experience and becomes a proselytiser for the phenomenon. I said to Steven, “I refuse to write a story about the first man to leave our solar system with the sole goal of setting up a McDonalds.” He said, “That’s exactly who I want.” (Laughs)

Saturday, November 16, 2024 at 6:26AM

Saturday, November 16, 2024 at 6:26AM  (Credit: Alex Ross Perry / Instagram)

(Credit: Alex Ross Perry / Instagram) The changing attitudes to the impact of the home video decades can be found in the announcement that the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) will be dedicating a strand in the 2025 program to the VHS heyday. As conversations evolve around streaming platforms and their impact on cinema going, IFFR presents HOLD VIDEO IN YOUR HANDS, a timely exploration of VHS culture, deeply rooted in community, creativity and unique viewing practices.

The changing attitudes to the impact of the home video decades can be found in the announcement that the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) will be dedicating a strand in the 2025 program to the VHS heyday. As conversations evolve around streaming platforms and their impact on cinema going, IFFR presents HOLD VIDEO IN YOUR HANDS, a timely exploration of VHS culture, deeply rooted in community, creativity and unique viewing practices. In a 2023 interview with website Cinema Scope, Perry (pictured, above), who worked at the iconic Kim’s Video Store in New York, said “Social relationships in video stores as depicted on-screen show that for about ten years, basically the entire ’90s, the video store was an inherently social space. Pre-internet, pre–message boards, like the record store or whatever, you had to go to learn and discuss, with employees, customers, friends.”

In a 2023 interview with website Cinema Scope, Perry (pictured, above), who worked at the iconic Kim’s Video Store in New York, said “Social relationships in video stores as depicted on-screen show that for about ten years, basically the entire ’90s, the video store was an inherently social space. Pre-internet, pre–message boards, like the record store or whatever, you had to go to learn and discuss, with employees, customers, friends.” In a similar vein is Jagannathan Krishnan cinema-verite documentary Videokaaran (2011; pictured, right), which will have a retrospective screening at IFFR. The acclaimed feature is a handheld odyssey through the world of underground video parlours, where audiences would gather in makeshift cinemas to watch videos projected on whatever flat, upright wall was available.

In a similar vein is Jagannathan Krishnan cinema-verite documentary Videokaaran (2011; pictured, right), which will have a retrospective screening at IFFR. The acclaimed feature is a handheld odyssey through the world of underground video parlours, where audiences would gather in makeshift cinemas to watch videos projected on whatever flat, upright wall was available.